Article I

A Story of Zen no Aikido * and Bananas

By Gaku Homma, Nippon Kan Kancho

March 20th, 2006

This first article was written from an outline of Homma Kancho’s teachings at a special fundraising seminar for orphanage support in Bangladesh held at Nippon Kan Headquarters March 18th, 2006.

*The word Zen in the title of this article does not refer to Zen Buddhism. The Japanese character is written differently and translates as “virtuous and respectable.”

I have written before, “People create the martial arts, martial arts do not create people.” Teachers and students together nurture each other and each grows in the process. If we are to more deeply understand the martial arts and ourselves we need to pursue our study through practice. Our training must be diligent and never ending. This is shuygo. Even someone who has become a famous instructor with their own organization must practice. If one does not practice shuygo with diligence there will never true understanding.

Sokaku Takeda, Founder of Daito Ryu Aiki Jujitsu, was a teacher who traveled throughout Japan teaching his art until his last days in the countryside of Aomori Prefecture. Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba from his days as a young man until the end of his life worked hard, practiced, and studied. His life was tumultuous at times with many successes and many failures.

Today you can find Aikido dojos in countries all over the world, and it is said commonly said that the Founder’s life was a great success. The late Morihiro Saito Shihan 9th Dan, who lived with the Founder from 1946 until the Founder’s death in 1969 had a deeper insight. “Toward the end of the Founder’s life, his students only knew the public image of a great man,” said Saito Shihan. “They did not understand the truth of his life. In truth, the Founder faced many hardships, much loneliness and disappointment in his life. I remember times when the Founder was forced to use donations left on the dojo shrine (tamagushi) to buy food, and relied on rice that was given to him by the families of students to survive.” This testimonial by Saito Shihan on the life of the Founder speaks to aspects of the Founder’s life that are not written about in most biographies.

These two martial artists, both Sokaku Takeda and Morihei Ueshiba lived difficult lives. Today their names are legendary, but what lies at the heart of their success is their constant dedication to shugyo. Both men accepted hardships as part of their practice and did not retreat. They worked through their difficulties as part of their life training.

So how do we approach our practice of Aikido. Some Aikidoka may not care to hear my opinions on the subject, wanting to do things their own way. Doing things “your own way” seems to be a current mood in our Aikido society today. For some instructors and students, Aikido is mostly about “magic and miracles”, not hard work and training and these people are usually interested only in their own perception of Aikido.

A Zen Buddhist Master (roshi) once told a story to his young students about the moment he achieved enlightenment. “One evening as I was walking in the moonlight through the temple gardens, I hit my shinbone on a rock. It was at that very instant that I achieved enlightenment.”

The next evening, all of the young monks in training could be found in the garden hitting their shins against the rocks.

If you give bananas to wild monkeys they will never learn to find bananas for themselves. The message of the story the roshi told the young monks is that true enlightenment is a personal experience. The story is a Zen Buddhist joke of sorts, a teaching parable. It was the master’s way of teaching the monkeys to find their own bananas.

After returning from a one-month teaching tour of Nepal, India, Bangladesh and Mongolia, I sat at my desk staring at the mountain of mail that had accumulated in my absence. As I began to sort through it I noticed a flyer for a summer Aikido seminar in the mountains. It struck me that this advertisement had been sent out quite early which meant either business was good or there was a little desperation in this mailing and business had not been so good of late.

I thought about these seminars and how expensive they can be — seminar fees, transportation, food and lodging expenses can add up. People spend a great deal to attend these seminars and fulfill their personal dreams. It is true that there are many rocks in the mountains, but as the roshi taught his students, “Hitting your shinbones on the rocks does not guarantee enlightenment.”

Every time I travel I become more convinced that there’s more to be learned by experiencing the world than by attending a seminar. I have had the chance during my travels to meet people as wise as the roshi mentioned in this article. I have known martial artists in developing nations whose Aikido practice and instruction is serious, dedicated, and pure. I have discovered that there is much to learn from those who are living on the “front lines” in countries and in conditions that many people cannot even imagine.

BANGLADESH

On this tour, the third country I visited was Bangladesh. It was in Bangladesh that I discovered a love and consideration for others, a caring and personal peace in the people I met that stood out vividly against the harshness of life there. The martial artists I met in Bangladesh correctly understood their position in their community and what they had to offer to the young and to the future of their country. They understood the educational value (kyozai) of the martial arts and were dedicated to creating a foundation for those that will follow them. Their approach toward their own practice and their teaching was very different from what I have seen in other more “developed” countries, and I would like to explain what I discovered about the martial artists on this journey to you.

The martial artists I met in Bangladesh truly understood that the power of a nation can be raised by supporting and developing its young people. They were correct in their position that education was the foundation for the future, not the pursuit of personal magic or power. Their actions were filled with a grace and sense of purpose that I have not seen.

THE JOURNEY TO BANGLADESH

Six hundred kilometers north of India’s capital city of New Delhi is the town of Dharmasala. Dharmasala is the home of the Dalai Llama, the exiled leader of Tibet and the Sukurakan temple. It was here that I left the other members of our tour and started the journey forward alone.

I took the night train south. In the early morning hours I found myself sitting on the open deck between the rail cars staring out at the countryside as the train slowly made its way back towards New Delhi. I suddenly realized that three hours had passed as I sat watching life in the India outback roll by.

Before this trip I had felt like I had seen and done many things, and that not much could surprise me. In my mind I could find an appropriate place to file similar experiences or feelings and had my own order for the world. This trip had already changed my perspective and the journey had only just begun. Scenes of life jumped out of the morning fog that had no place of order in my mind. So many images danced before me that I soon even lost my sense of time.

From New Delhi I boarded the plane for Bangladesh, my brain still swimming with images of India. “I still can’t organize my thoughts” I said to myself. I realized what a small person I had been; standing all the while on the hand of Buddha while thinking I knew everything there was to know. I laughed at myself, thinking how much more there was to learn.

The flight only took one hour and forty minutes. From the window as we descended toward the airport in Dhaka, I looked out at what must have been fifty huge smoke stacks of what I was to learn were brick factories dotting the land below. Once when landing in Managua, Nicaragua I was surprised by the abandoned cannon bunkers that lined the runways on our approach. I hope, I thought to myself jokingly that these chimneys were not full of missiles!

The plane landed at Zia International Airport in Dhaka, and I was met by Shaaeekh (Maji) and company, who had originally invited me to Bangladesh. Maji attends the university in Dhaka and lives with his parents who own a hotel adjacent to the Kamlapur Central Train Station.

On our way from the airport, Maji introduced himself and then said quietly “Bangladesh is a pretty poor country.” I heard what he said, but I said nothing, letting his comment

pass. In other developing nations I have visited in different parts of the world I have heard that said many times. It is a difficult subject to respond to.

By what measure do we judge what is rich and what is poor? As I looked around while we made our way to the hotel, I saw markets filled with vegetables, meats, fish, fruits, clothing, decorations, crafts etc. Bangladesh had electricity, schools, festivals, celebrations and a religious presence in the people that seemed manifest in every aspect of their daily lives. By the standards of others, the people I was meeting on this trip may not have a lot of monetary wealth, but they possessed a richness of heart that is evident in the way they take care of those less fortunate around them.

A bountiful harvest in Bangladesh

- Butcher shop row in Dhaka.

- Very friendly people!

- Traditional Bangladeshi hats (topi) for sale.

- Speakers for sale, used for broadcasting prayers at the many mosques.

Some of us that live in “developed” countries might use an international monetary standard to measure and rank countries by their economic wealth, drawing a line somewhere in the list designating countries as “developed” and others as “developing” or “poor.” These distinctions and labels I feel are not fair. It is difficult to judge all cultures by only one standard.

In Dhaka, Bangladesh, a two liter bottle of mineral water costs 3 cents (U.S.), and a haircut at the local barber shop costs 4 cents (U.S.). In the United States, that same bottle of water might cost $2.50 or more, and even a cheap haircut these days runs about $15.00. It is difficult to compare the numbers unilaterally.

Sometimes travelers revel in how “cheap things are!” in certain countries compared to their country of origin which can be quite inconsiderate to the local population of the country they are visiting. Each country has its own economic reality and I think it is important to respect each countries individual standard of living. To do this, we need to look beyond a price tag to the all of the factors and conditions involved and appreciate the hospitality that is being offered, not how much it costs by our standards. Just because we might spend $2.50 for a bottle of water where it might cost 3 cents elsewhere does not qualify our country as being “rich.” I think Maji should be quite proud of the fact that a bottle of water costs 3 cents in Bangladesh!

A FATHER’S INSIGHT

Majis family. Left:Homma Kancho, Front center: MD Matitar Rahman Sarkar,

Front right Shaaeekh (Maji).

Maji’s father, Mr. MD Matitar Rahman Sakar is a retired Deputy Secretary for the government of Bangladesh. Mr. Sakar was very involved in Bangladesh’s independence from Pakistan and the development of this emerging nation during his career. During a visit, we sat down to chat. Mr. Sarkar spoke softly in perfect English as he told me about the current situation in Bangladesh. He also said, “I am familiar with the story of the life of the Founder of Aikido, Morihei Ueshiba, and I find it very interesting. His life did not always go smoothly, and his accomplishments were not always easy to come by. He had many successes but also he suffered many defeats and failures as well. That, is one of the reasons I admire him. Today the martial art of Aikido is practiced all over the world as a result of his life’s efforts. I want my son to understand the life of the Founder and learn from Aikido. The struggles the Founder faced in his life are very much like the struggles we face here in Bangledesh. The more my son understands the life and art of the Founder Ueshiba, the more prepared he will be to deal with life in Bangladesh both now and in the future.

Training and mastering a martial art is not easy. I think you understand that.” Mr. Sakar said with a big smile. “Aikido does not have tournaments nor does it promote fighting. It has this teaching in common with teachings of Islam. For this I respect this art very much.”

For Mr. Sakar to wish the same kind of life experience as the Founder for his son reflected on his wisdom and his years of service to his own country. I respected his words and point of view very much.

A DIFFERENT POINT OF VIEW

Martial artists I met in these developing nations seem to seek and find something in their practice that we miss; and they practice very hard. Supporters, educators, even governments in the countries I visited look to the martial arts as a form of education for their young people. In less than ideal practice conditions, in less than comfortable living conditions, instructors that I met on this journey are devoted to their art and its teaching, and, they are supported by their communities.

As Maji’s father indicated, many of the martial artists I met in Nepal, Bangladesh and Mongolia identify their own life struggles with the life of the Founder Ueshiba. They identified with his spirit. It is the Founder’s life that is a primary inspiration. The art of Aikido is secondary. Instinctively these martial artists understand the opening sentence of this article, “People create the martial arts, martial arts do not create people.” In their understanding, it is the character of the man first, then his work. If the Founder’s work had been something else than Aikido it would be of less consequence, it is how he dealt with his life that is important to them. They study the way of the life of Morihei Ueshiba to understand Aikido. They do not take his art of Aikido and try to dissect it to find its meaning and the man behind it.

For three mornings in Bangladesh, I visited a private school in Dhaka named the Paris International School. The name infers a school that is quite well off, but even the Principal Mr. Hossan described his school as “a very poor school indeed.”

Principal Hossan opened the Paris International School in 1970, and has been providing morning and afternoon classes daily ever since. The Paris International School has about 300 students that range in age from two and a half to ten years of age. There are twelve teachers at the school, and monthly tuition for students is $8.00. “I do not receive any financial assistance from the government” said Principal Hossan with a mixture of pride and a little sadness.

Every morning before classes, martial arts are taught in the courtyard by A.B Z. Nain Sensei who has been teaching at the Paris International School for nine years. The bricks that pave the courtyard are uneven and in bad repair yet the children practice diligently every morning in bare feet. “Every child is my child.” said Nain Sensei.

Nain Sensei’s primary occupation is in the meat exporting industry. He and all of the other adults that help out with morning practice volunteer their time before they go to work in the mornings.

- Paris International School.

- School building.

- Sitting with mothers on the sidelines watching morning practice.

- School begins at the sound of the bell!

I truly enjoyed teaching and practicing together with the students at the Paris International School. The children were so innocent, well behaved and eager to learn that it was a delightful experience. After practice, I was invited to the principal’s office for tea and steamed bread made from rice flour. It was a simple treat, but quite enjoyable after an early morning practice. Over tea I listened to the principal and teachers and through their words I could feel their sense of purpose in teaching the martial arts as part of the education they offer to the children. I thought their understanding of the importance of the training was profound. I was also surprised to discover that they too were familiar with the life of the Founder Ueshiba and knew a great deal about his adventures and misadventures. They discussed what had happened in the Founder’s life and were able to relate some of his experiences with their own.

- Right: Nein Sensei, Left: Principal Hossan

- Talking in the principal’s office

In Asia, the heroine of this drama is widely popular. Many people can relate to Oshin’s experiences, her meager beginnings, and her drive for success. It is a story that offers hope that anyone can make it if they try. Even the name Oshin has become a popular cry when doing something physically demanding to gather strength and energy. Parents council their children “remember Oshin and be strong!” In towns and villages all over Asia it is still common for everyone to gather around the television to watch Oshin; even if there is only one television in town!OSHIN

There is a famous TV drama in Japan called Oshin. This drama has been translated into scores of different languages and has a following in over fifty-nine countries. Especially in Asia, this drama is a big hit. The drama Oshin is set in the Japanese countryside about 100 years ago, much as Japan was during the Founder’s lifetime. At that time in history, Japan was a developing nation too. The heroine of the story is a woman named Oshin who came from very meager beginnings. Oshin had a very hard life filled with many struggles. In the drama, through her own grit and determination Oshin overcomes all obstacles to become the owner of a large supermarket chain.

- Homma Kancho with students.

- Six passenger school bus rickshaw!

The understanding of the Founder’s life by the martial artists I had met on this trip is very different than the understanding of the Founder and Aikido I have heard from Aikidoka in developed countries like the United States, Canada, England, France etc. In many cases Aikidoka in these developed countries seek to find in Aikido something for their own personal development. They practice Aikido for their heath, for self defense, to find love and harmony. They search to develop their ki, to become successful in business and even to improve their golf game. The practice of Aikido for these Aikidoka is a means to get something else from its practice. “I want this, I need this, and Aikido will help me get the things I want to become successful and profitable.” This is the battle cry of some Aikidoka I have heard. The needle of this compass points in a completely different direction than the needle on the compass that guides the martial artists I met in Bangladesh and Nepal.The Principal Hossan and his staff were all fans of Oshin and likened the Founder Ueshiba’s life struggles to hers. They took direction from the Founder’s life like the point on a compass, and it was remarkable to me that someone like the Founder who had been so influential in my own life had affected this group of school teachers in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

I found that I very much respected Nain Sensei and the others for their respect for the Founder and the purity of their practice spirit in such challenging conditions.

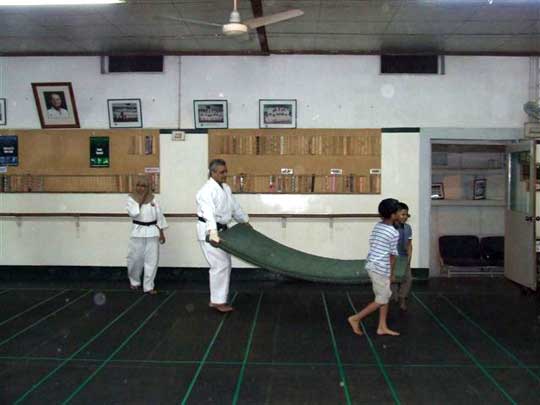

In the evenings I went to visit Kazi M. Quasi Sensei’s dojo in a wealthier area of Bangladesh. Quasi Sensei was educated in the United States and is a successful businessman in the Dhaka garment industry. His property houses the dojo he opened for young people in the area to come and practice the martial arts. Quasi Sensei trained in Wado Karate in the United States and teaches Karate to his students at his dojo. He is not a member of any local martial arts association or organization as he is not interested in position, honors or the regulations that accompany them. Quasi Sensei is busy with his own practice and the teaching of his students. This dojo is also open to the practice of Aikido. In the Bangladesh community he is one person who understands and supports its practice. Quasi Sensei said, “I opened this dojo for the young people and their future in Bangladesh.”

After the first evening practice, as we left the dojo, I was surprised to see a fleet of luxury cars (complete with drivers) lined up outside. They were all there to take the students home after practice. After the students had left Maji and I hopped into a bicycle rickshaw. I turned to Maji and said, “Wow the students were all picked up in such nice cars and with chauffeurs no less!” Maji replied, “We have a chauffeur too!” nodding toward our rickshaw driver. This made me laugh as we headed toward the crowded main street leading back into the heart of Dhaka.

Maji continued quietly in a matter of fact tone during the ride, “The people that are rich here hire people to work for them which allows for many people to be able to take care of their own families. In this way they are helping people too.” As we rode, I remembered that I had heard this said before in Brazil, Nicaragua, Mexico and other countries. It made sense. Those with wealth supported their community and their local economies by hiring chefs, gardeners, house keepers, drivers, mechanics, etc. Those that are hired can in turn help support others. In this way, the hiring of every person brings goodness not only to those hired but also to the ones who are able to do the hiring. There are of course inherent problems in all countries where there is a vast distance between the rich and the poor, but in a country like Bangladesh where the government is still incapable of supporting the problems of the indigent, this kind of hiring system is a way for a community to care for its own.

AHAN IN BANGLADESH

Maji took me to visit the Dharmarajika Buddhist Temple. This was our first step in doing research for the beginnings of AHAN (Aikido Humanitarian Active Network) Bangladesh. At the Dharmarajika Buddist temple over 500 orphaned boys are clothed, housed and fed. Taking care of this many children on a daily basis is a daunting task. We were told that it took 160 kilos of rice alone to keep the orphans fed. Without the help of many people in the Dhaka community this would be an impossible task.

- Temple kitchen facility.

- Volunteers in the kitchen.

- Children waiting for lunch to be served.

- A mound of rice with sliced daikon (radish) salted curry soup.

- Mealtime is a favorite with the kids!

- Homma Kancho in the children’s living quarters.

Young boy teaching himself.

Maji and I also visited the Tara Majsid Madrasah Islamic Mosque, which also cares for about 150 orphaned boys. At the Dharmarajika Buddhist Temple and the Tara Mosque the support of individuals in the community is vital to the survival of these children. At both facilities I saw many people that were volunteering their time to help. I watched with my own eyes as volunteers cooked, cleaned, washed and taught the children under their care. It touched my heart to see how rich the hearts of the Bangladesh people are, manifest in the way they care for and help each other.

- Boys studying at the Tara Mosque orphanage facility.

- Homma Kancho with their teachers.

Of course, everything I saw in Bangladesh was not completely positive. I met people who told me about terrorists who operated in their country and others that complained bitterly about the caste system that still bound people to generations of servitude or worse. Poverty and misery were prevalent in some places and were specifically pointed out to me at times. One question that still remains for me is; what happened to the orphaned little girls? I did not see any in the orphanages I had visited…When I first sat down to write this article, I found it difficult to describe the experiences I had in Bangladesh. I “hit the wall” as they say. I did not want to write anything about my experiences in this country I had been invited to visit that might give the wrong impression or cause a misunderstanding.

A scene remains in my memory of a five-year-old boy with no arms or legs sitting in a cart in the street. He was begging loudly for anything that might come his way from those passing by. That little boy affected me greatly.

Because I saw these things I know that this is part of life here, but to judge Bangladesh using my life experience as the measure, I feel is unjust. I think it is better to focus on the good of the people of this country that are working for the future of their people. Energy is better spent to support and confirm their convictions and their actions. Some of the images in my mind I will keep forever, and some day I hope we can look back and marvel at how far things have come. The people of Bangladesh like Oshin and the Founder Ueshiba struggle against many obstacles to reach their goals. We stand in support of their efforts and hope to be able to help in any way we can.

ZEN NO AIKIDO

I feel I have an obligation to the Aikidoka I have met who pursue their art in less than ideal conditions with dignity. My obligation I believe is to practice and teach Zen no Aikido. I am not referring to Zen Buddhism here. Zen, in this instance translates as being virtuous and respectable or pure.

For me, becoming sidetracked by some of the trappings of Aikido like designer keiko gi andhakama, $300.00 bokken and jo sets, designer bags and expensive retreats are not part of Zen no Aikido. To grow lazy in one’s practice, to forget to study or face new challenges is not Zen no Aikidoeither. To just punch the clock when teaching Aikido or teach Aikido by capitalizing on flowery phrases or movies of violent Aikido fiction is not the kind of Aikido I wish to share with the martial artists I have met on the “front lines.”

If you believe that Aikido is the martial art of love and harmony in the world, yet practice this concept by sitting in front of the dojo altar and praying for peace, it will forever be illusive. We must as individuals stand up, turn around and look to the Aikidoka who practice without all these trappings of our “civilized” world, to the Aikidoka that practice sometimes even without a mat available within their means.

This summer instead of signing up for another expensive seminar-retreat, think about what you might be able to share with our fellow Aikidoka in developing nations. Discuss ideas with your dojo friends; there are things that you can do. By taking even a small step, there is so much we can learn about Zen no Aikido in our own lives. Where you used to pay to be given bananas, you can find the bananas yourself.

As a small independent organization, Nippon Kan General Headquarters is involved humanitarian projects in many parts of the world. We have developed these projects to help us understand the meaning of Zen no Aikido, and we have made many friends along the way. For a dojo to grow and be happy, I think it is more important to think about what you can share and give to others than what you might want for yourself.

*****

To the martial artists in Nepal, India, Bangladesh and Mongolia, this is only a small part of what I learned from all of you on this journey. I sincerely thank everyone for sharing with me, and I hope to see all of you again very soon.

*Permission was granted for the use of all the photos in this article, especially the photos taken at the orphanage facilities in Bangladesh.

,

March 20th, 2006

Gaku Homma, Nippon Kan Kancho

ARTICLE II

Martial Artists in Kathmandu, Nepal

In the pre-dawn hours in Kathmandu, the streets are lit by methane torches. Yak butter candles shed frail light in the internal darkness of the shops and temples that line the awakening streets. As shopkeepers and homemakers begin to stir, five hundred to one thousand young people gather at the Rangasala Soccer Stadium each day. These young people are not gathering there as the sun begins to rise to play the game of soccer.

The space underneath the stadium, where concessions and restrooms would be, is divided into small individual spaces that happen not to be fitted with the luxury of electricity or plumbing. These spaces are home to over twenty different martial art organizations and dojos which hold martial art practice simultaneously each morning. Sometimes there are more students than room in these spaces and classes spill out onto the grounds or are held outside near the pool training area.

In all of my travels I have never seen so many different martial art groups practice together at the same time. The soccer stadium and all of the activities housed there (including soccer by the way) fall under the umbrella of supervision of the National Sports Council of the Nepalese government. The Nepalese government is very wise in my opinion to recognize the value of this training in the development of their countries youth.

It was a wonderful discovery to find how hard all of these students practiced, and how well mannered they all seemed to be. Most of the dojos that were housed at the stadium were Karate dojos that focus on punching and kicking skills. You would think that having so many different types of dojos in such close proximity to each other would make for the beginnings of a riot! It was rewarding to find that they practiced very respectively of one another.

I was to find out that these martial artists practice so early in the morning because most students worked or went to school during the day or evenings, so the most popular time for practice is in the morning before work or school begins. These dojos did not operate to make a profit, students practiced to practice, and they practiced hard.

I had been invited to teach Aikido by the Kyokushin Karate dojo on this trip. When we arrived for practice at the stadium the sun was not yet up, and the dressing rooms were lit be candlelight as we changed for class. Finally the sun rose high enough in the sky to light the dojo better for training. All of the students attending were sincere and open to learning something new. After practice all ten of us from Nippon Kan were invited to have breakfast with them. It was a breakfast of toast, boiled eggs and chai; simple but quite delicious after two hours of training. We all were very appreciative of our host’s gracious hospitality.

The future of any country is based on the education and strength of its young people. The Nepalese government is aware of this, and does its part to help create a good foundation of support for the young people of Nepal. The National Sports Council supports and protects martial art education in Nepal as a positive educational tool. Not only the government, many civilian sponsors support the martial arts and offer their professional talents in assistance.

Domestically we found Nepal is a state of political unrest during our visit. In fact, the day before we arrived, Kathmandu had been under a twenty-four hour curfew enforced by the national military. We were a little nervous before our arrival, but with the communication we had with the Nepalese martial art community, our fears were put to rest. Despite any political unrest, we found that the young people in Nepal traditionally respect their elders, and that the relationship between generations is strong. Watching these young people in their practice in Kathmandu made my heart swell with pride.

About the time the sun had fully lit the dojo, it was time to end practice. As we made our way back through the narrow crowded streets we watched as locals paused briefly at the countless Hindu and Buddhist shrines to give their daily offerings. There was a holiness in all of the hustle and bustle of the daily lives of the people that was very, very real.

I hope that the political climate in Nepal resolves itself quickly and that the Himalayan gods that live in the Kathmandu valley continue to shine down as they have for thousands of years. Peace, we hope will remain with the Nation of Nepal.

March 12, 2006

Gaku Homma

Nippon Kan Kancho