by Gaku Homma

Nippon Kan Kancho

February 15th, 2005

Twenty minutes before landing at the Tribhaun airport in Kathmandu, I looked out of the window of the plane as the Himalaya Mountains appeared; rising from the blanket of clouds with such majesty I caught my breath. A man, seated in front of me, stood up excitedly when he saw the mountains and began waving to fellow passengers and speaking excitedly in his native Nepalese tongue. He peered intensely out the window and continued to express his excitement and joy.

I found this somewhat surprising, but his actions did not seem to faze the other passengers who just nodded at him with smiles. There were tears of joy in his eyes, and he made no attempt to hide the emotions the sight of the mountain peaks brought to his heart. He continued in his revelry along with the other passengers until the flight attendant gently reminded him to sit down and buckle up for landing. Even though I could not understand his native tongue, I did understand the word Himalaya, Himalaya which he repeated joyously over and over again.

As the plane descended into the clouds, I imagined that this gentleman had not seen his homeland for a very long time. I tried to imagine the journey he might have been on that took him away for so long. From a country with the third lowest income level in the world, many Nepalese seek work in other countries. Whether this gentleman was returning with pockets full of gold or full of disappointed dreams, his joy was infectious and I found myself celebrating his return with him.

I am told that Kathmandu, the capitol of Nepal is a city that has more religious statues than people, that the people of Kathmandu live at the base of a mountain of gods, much like the Himalayan Mountains that surround them. I am told that their lives revolve around their beliefs and the life I was to experience here was to be a rich one. I abandoned my thoughts for experience as I climbed into my first Nepalese bicycle drawn rickshaw and headed for the hotel.

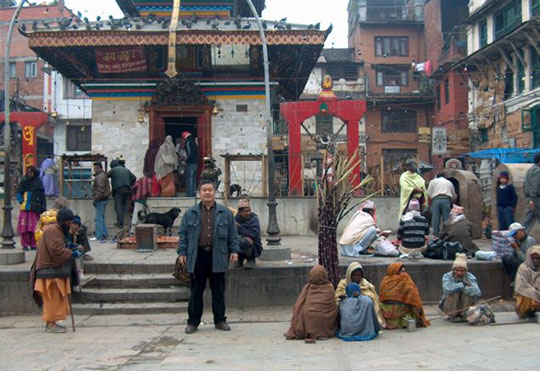

Busy downtown Kathmandu.

Small cars passed, missing each other by mere inches on the narrow winding streets. The streets were not host to only cars, there were horse drawn carts, human manned carts, wheelbarrows, motorcycles with two, three or four passengers, bicycles by the hundreds piled high with furniture, bundles of vegetables, and wares for sale. There were strong and wiry men colorfully dressed manning rickshaws and pedestrians by the score. I watched in awe as we passed a man that was actually carrying a full sized sofa on his back. Another man bobbed and swayed through the crowds with two baskets piled high front and back on a stick balanced delicately on his shoulder. Mixed among this lively throng of humanity were cows, dogs, and goats that also meandered through the right of ways. Every living creature made their own noises, warning others of their passing with a melody of sounds.

While all of this was going on IN the streets, the sidewalks were also busy with activity. Vendors selling all types of wares, some with only a single newspaper as a display for goods, lined the streets as far as I could see. There seemed to be no apparent traffic laws or rules for the road and yet I saw no collisions on my rickshaw ride. I became aware of the intrinsic rhythm in this seeming chaos. Everyone gave way to one another. I saw no fighting or anger or impatience in the crowds. Every intersection looked like impending disaster to me, and I thought there would be no way to move forward through the crowds. I still am not sure how, but the tangles seemed to unravel themselves and we would travel forward uninhibited towards our destination.

The only real traffic snarl I witnessed was caused ironically by a uniformed policeman that was making futile attempts at directing and controlling the traffic to his liking. Those who passed us by on bicycles or rickshaws worked hard peddling to keep up with the pace of the traffic. I found myself tensing and pushing too, trying to help my rickshaw move forward if only with my thoughts.

In the last few years I have been able to travel to many parts of the world to teach Aikido or to work on developing humanitarian activities with AHAN (The Aikido Humanitarian Active Network). It has been a privilege to have local hosts in each country to guide my way in their native lands; to be able to see and experience things that a traveler cannot experience on their own.

One of my reasons for coming to Nepal was to learn about the Martial Art community here. My first stop I learned was to be Dasrath Stadium where many groups of martial artists gathered early each morning at dawn to practice.

On the night before my visit to Dasrath Stadium, I asked the rickshaw driver if he could meet me at my hotel at 5:30 am. the next day. To make sure he was not late for our appointed meeting time, the driver slept that night in the security room of the hotel. I am sure his accommodations were not the most comfortable, but I guess it was better than peddling across town to wherever his home might be.

The next morning as we set off for the stadium, the city was still dark except for the hundreds of butter candles that glowed a beautiful orange from the temples and shrines. As we made our way, I saw shop owners preparing for their busy day ahead in the light of single dimly lit light bulbs.

The trip by rickshaw from the hotel through the winding streets dotted with temples and shrines took about a half an hour. The stadium was located next to the Nepalese Army Training Center and is the largest soccer stadium in Nepal.

- Karate signs in a row.

- Karate practice outside.

Different Karate groups practice side by side

Different Karate groups practice side by side

On the ground level underneath the stadium were many smaller gymnasium spaces. As I entered the gates and got closer to the shuttered gymnasium fronts I was met with a surprise. Each space bore a sign, and the first ten spaces in front of me that I could see were hung with signs for Japanese Karate and Chinese martial art dojos. Through the shuttered doors below each dojo sign came a faint but familiar sound. It was the sound of “kiyai” or the voices used in martial art practice. The familiar sounds came from the first floor gyms, and also from a second level somewhere. I soon noticed that kiyais could be heard coming from the parking lot areas outside the stadium and more could be heard from adjacent buildings. As I looked around, following the sounds, I glanced at my watch. It was now 6:00 am.

I went inside and began to walk past gym after gym. I have never seen so many styles of martial arts practiced side by side anywhere in the world especially before sun up! Each gym looked to have an average of thirty students, some numbered closer to one hundred. Even within one form of martial art, there would be several different style groups practicing at the same time. Somehow I did not look out of place as I strolled through the stadium and everyone was polite, gracious and helpful; offering me assistance as I passed by. One young instructor stopped and introduced himself, and I introduced myself to him. He studied me for a moment before disappearing. He returned shortly to my surprise with a worn and tattered copy of my book “Structure of Aikido”, and asked me to sign it. Where on earth he got that book I guess I will never know!

All of the gyms I passed by were practicing Karate, Kempo, or Taekwondo styled martial arts. The only exception I saw was one group practicing Judo. The stadium facilities I was to learn, are run by the National Sports Council which organizes most all of the martial arts taught in Nepal. I was informed later by a National Sports Council staff member that the reason martial arts like Karate and Kempo are taught in Nepal is because these arts can be practiced anywhere with a minimum of equipment. “They can practice almost anywhere”, I was told. “Judo however requires mats and a permanent facility which is harder to afford on our budget. It used to be that Martial art groups were not organized by the National Sports Council. These arts became so popular however, it was decided by the Council that it would be better to register and organize the groups and practices. By being able to provide a facility for these practices, it is easier to keep our young people in control. There used to be an Aikido group that practiced here, but not presently”.

After spending about an hour at the stadium, I returned to my rickshaw driver and we headed off back to the hotel. By this time, morning rush hour had begun, and what was a thirty minute trip to the stadium became an hour and a half trip back!

Along the way we came upon a steep hill, and the rickshaw driver was pedaling heavily in a standing position just to keep moving forward.. It seemed like the whole world was behind us, honking impatiently as we attempted to scale the hill. Finally the driver ordered me out of the rickshaw with a wave of his hand, and I began to push the rickshaw from behind. I had hired the driver for four days, and I felt like we had formed a bond. I am sure it looked a little strange, but I didn’t mind helping at all. After we had negotiated the hill, I decided I wanted to try to “drive” the rickshaw. The driver hopped into the back and I attempted to maneuver the rickshaw forward.

I didn’t even make it ten yards. It looked so easy! But it was very difficult to steer, and keep my balance and momentum going at the same time! I could not for the life of me imagine how to deal with any traffic should I encounter it. The driver smiled at me knowingly, and we switched places. I decided that my job teaching in the dojo was MUCH easier than his job any day!

When we arrived back at the hotel, I was surprised to see that a few people I had met at the stadium were waiting for me. One of them said “While you are here in Nepal, we would very much like to practice Aikido with you. There are other students who wish to practice also”. Since one of my goals for visiting Nepal was to find out if there were any practicing Aikido groups, and offer any assistance I might have, I happily agreed. After giving me the time and location for the practice, they left to go on about their day.

The practice was to be held at a Nepalese Military Facility. When I arrived, there were about forty students waiting for me. Most of them were from the military or police services along with a few young karate students. Out of the forty people, there were about sixteen that had had any experience with Aikido at all.

One gentleman was a security guard for the former Prince Dipendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev, and he had served as practice partner for the Prince who had achieved his black belt rank in Aikido in London while he attended his studies. The guard was happy and nostalgic about practicing again.

Before practice and I looked out at all of the body guards and policemen before me. “This is going to be interesting”, I thought to myself. “These are big and strong men, and few have any Aikido experience at all. I know that they are looking to see hard effective techniques. They want to learn things they can use now; I don’t think there is time to start with tenkan steps and rowing exercises! What can I teach them? , I thought with growing anticipation.

The space we had for practice had no shrine, or front for that matter, so I just picked a direction to be the front and had everyone line up. We began with a silent meditation with closed eyes. After the meditation, I opened my eyes, bowed, turned around to face them, and bowed again. As I did this, I realized that the first thing I had taught in Nepal was “rei”; the spirit of respect and greeting that is an essence of Japanese martial arts. The Nepalese are a religious people by nature and by culture, and these gentlemen were trained, disciplined soldiers. The concept behind “rei” was easily understood and assimilated, and made for a wonderful start. The mood now set was friendly and sincere, and I was able to follow my beginning Nippon Kan class format with these new Nepalese students.

On the morning of my sixth day in Nepal, I awoke at 6:30 am and flipped on the television in my room. It took me a moment to realize that every station was broadcasting the same image with the same message. I did not understand what was going on, so I went down to the lobby to get some tea and inquire about this oddity. The entire hotel staff was gathered in front of the television in the lobby, so I had a feeling something was going on. At 10:00 am, King Ganendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev came on the television and began to give a message to the people of Nepal. Without asking, someone translated his words for me so that I might know what was going on. It seemed the King had dissolved the cabinet and had retaken control of the government. They were calling this the Kings “coup”. Television and radio stations had been taken over, and telephone or internet communication and transportation had been cut with the outside world.

I looked outside to see heavily armored soldiers manning the streets, fingers on the triggers of their weapons. Some soldiers were masked; others on horseback, all were armed and ready; watching carefully as locals gathered in groups to read special edition newspapers that were being distributed about the take over. Since these special edition papers were on the streets not thirty minutes after the King’s announcement on the television, it was apparent that this take over was well planned and organized. The special edition newspapers about the Kings take over provided some relief for locals who worried that this might be a government take over by Maoist communist groups.

- Soldiers patrolling the streets.

- Soldiers on horseback move towards their positions.

- People pray while walking around the pagoda in circles.

- Life as usual, daily prayers.

I had so been enjoying the flavor of Nepal, and the holiness of live here. It was quite a shock back to reality to see armed, masked soldiers patrolling the streets! What a contrast from daily prayers to guns. However, even though the peaceful feeling I had experienced in Kathmandu the day before was interrupted, I did not feel worried or fearful for my own safety. I did not fear for myself, because the people I saw around me did not. Life somehow started forward in an almost normal pattern. The people I saw seemed to be going about their normal routines. The money wheels at the temples kept turning, the bells rang, incense and candles were lit, and somehow, an air of calm, normality filled the city around me.

That evening a military officer came to my hotel. He had attended the practice I lead earlier in the week. He said he had come to warn me that I had better hurry and get out of Nepal. “It is safe here right now” he said, “but there may be demonstrations that follow. It might be even more difficult soon to get a flight out of Nepal if you do not hurry”. With that he bowed toward me with his hands held together in front of him and said “Namaste”, shook my hand and left.

The next day, I made my way through a heavily guarded airport, and with great luck, made my originally scheduled flight on time!. Security at the airport was extremely tight, and everyone was searched carefully. It seemed they were especially looking for recorded images of the current internal situation, and film, digital chips and tapes were being confiscated.

In my case, I “donated” a new disposable camera to the guards, and they also took the chip that was in my digital camera. That chip contained photos of the practice at the military base, and also of the military patrols after the take over. They looked at me more than a little suspiciously, but after accepting my “donation”, let me pass. Luckily all of the other digital recordings of my visit to Nepal I had kept in another pocket and they had remained undiscovered. It would have been a terrible shame to have lost all of my photos of Nepal.

As I walked toward the plane I remembered that I had promised to teach one more class before I left, but with the turn of events, I was unable to even say goodbye and thank you to the many people who had made my stay in Nepal a wonderful one. On this trip I was able to meet with students who were interested in learning Aikido. In the future, this is something I hope I will be able to help with, and some day there might be an opportunity for an AHAN project in Nepal.

As I waited for my flight I wrote notes to myself about an interesting situation I had observed during my visit. I had learned first hand, that Nepal is a country that is in need of support, but it is not a poor country. It is one of the richest countries I have visited with its wealth of history, culture, beauty, and wisdom. The people of Nepal are rich in heart and have deep religious beliefs and spirit.

People from all over the world have recognized the wonders of Nepal, and there are many non profit environmental, historical (restoration and preservation) and humanitarian aid organizations that have offered support to this land. In fact, I was stunned to find out, that there are between 15,000 to 20,000 different non governmental charity and non profit organizations represented in Nepal. The money generated by this body of organizations is larger in sum than the Nepalese National revenue. I also learned from a number of reputable sources here that many of these organizations are scams or fronts, and that any moneys collected by some of these groups never reaches the intended in need.

One authorized Nepalese Non Government Organization Staff member told me “Tourism is Nepal’s leading source of income, and we are grateful for all of the visitors that come to Nepal. Unfortunately problems like unsubstantiated Non Profit organizations are also a problem that has manifested itself with the coming of the visitors as well.

Visitors measure the standard of living in Nepal by their experiences in their own country. They think the lifestyle here is poor and sad, and they give us money or things. In the West, a dollar is just a dollar to spend on soda or the like. Here, a dollar is BIG money. If a visitor pledges one hundred dollars a month to a non-profit organization in Nepal, and the organization cultivates ten sponsors, this one thousand dollars of monthly revenue is e equivalent to six months of average working wages. It is understandable how someone might think that this is an easy way to make a lot of money, but setting up charitable organizations as fronts for personal profit injures many; from the visitors that may be raising money back home to generously send in aid to those who never receive the support intended for them. Disreputable organizations like these endanger the validity of authorized reputable assistance organizations and lowers the reputations of Nepalese organizations in general”.

During my visit I was approached many times young men who hung around the temples and tourist attractions. I watched them prey on tourists, soliciting donations for non profit organizations. If I ignored one of these young men when they approached me speaking English, they would soon switch to Korean or Japanese. If none of these multilingual solicitations worked, their words would turn more cursory in nature as they turned to fresh prey in defeat.

In the capital city of Kathmandu alone there are dozens of world heritage historical sites, of which most I saw were in disrepair. I saw monuments and works of art that you would see behind glass in a climate controlled museum in the United States that were covered casually with a blue plastic tarp to keep off the rain. World support IS needed in Nepal for among other things to preserve their wonderful history and heritage. It is important however to be careful to check the credentials of any assistance organizations before making contributions, and to make sure that funds go directly to the projects for which they were intended.

- Current ongoing preservation of historic monuments.

- Infrastructure systems such as water and sewer lag behind growth in Kathmandu.

The price for admission to historical monuments is $15.00 US for tourists, which is a handsome sum in Nepal. You do not get a ticket or receipt in return for your $15.00 donation, and I have my concerns about where this money actually goes. Unless this system is tightened up, I fear that it will be a very long time before the blue tarps are replaced with more permanent preservation solutions. Nepal bases its economy on tourism. These monuments are a national historical and monetary resource. The importance of their preservation is not only to remember the past, but to secure the future in Nepal as well.

Before my visit, Nepalese friends I have in Denver gave me gifts, letters and messages to give to their families back home. From each person I was given small sums of money to be offered at the local temples and shrines near their homes. Even from so many thousands of miles away from their home, my Nepalese friends still live in their hearts under the Himalaya Mountains. No matter how far away, they do not forget their home, their gods and their families. It is our dream for the future at Aikido Nippon Kan Headquarters to be able to support Nepal and its many people through the teaching of Aikido.

Many thanks to all of the people who showed me so much of their country, both here and in Kathmandu. I hope to return soon, as soon as the rifles and guns disappear and the peaceful wonder of life in Kathmandu prevails.

.

As I boarded the plane to leave Kathmandu, I thought of the young man on the plane coming into the capital city, and the glee he showed at the sight of the mountains of his homeland. I imagine now that he has been reunited with his family and that is was a happy reunion.

What is happiness…what is wellness…to be happy we need money…but you can’t buy happiness…like counting sheep, I pondered this question as the plane climbed high over the Himalaya Mountains. It was not long before I fell fast asleep.

Gaku Homma

Nippon Kan Kancho

February 15th, 2005

*authors note

Due to the sensitive nature of the political unrest in Nepal, any reference to specific names, places or people were not included in this article. All Aikido practice photos at the military instillation were confiscated by security at the Kathmandu airport. If you have any questions or information about Aikido in Nepal, please contact Nippon Kan at info@nippon-kan.org

To try to describe my impressions of the people of Kathmandu in a few pages is truly inadequate and an injustice to the hearts of these people. I think to truly understand the Nepalese people one has to come here.